Dedicated to a new age of restoration

Mural doctors

Commonly seen "diseases" affecting the murals include cracking and flaking, as well as efflorescing that is caused by changes in temperature and humidity of the caves, and the deposition of salts.

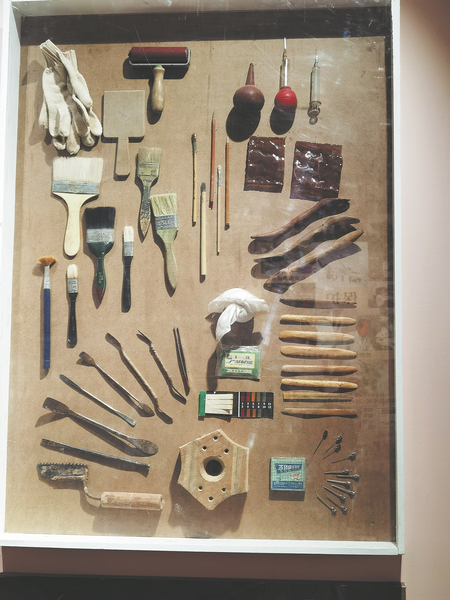

To restore a mural requires an all-rounder. The restorer should know painting, master the skills of a mason and have some knowledge of chemistry and physics, to be able to recognize the problems, their corresponding causes and deliver a solution. They must also select proper materials and tools, and conduct experiments, before formally carrying out the restoration and evaluating the effect afterward.

For example, dealing with cracked murals with small flakes curling up usually involves removing the dust, injecting adhesives, backfilling the painted layer, then rolling and pressing to flatten the edges.

Ancient mural painters applied pigments made from different ingredients — cinnabar for red, for example — resulting in damage with different traits and to varying extents. The tricks of restoring these murals, therefore, often lie in a different level of adhesive used and timing for the operation, which requires years of learning and practice.

The restoration should respect the original work and aim to maintain the status quo of the murals rather than repainting them, Li says.

Even at the height of summer, when temperatures soar to nearly 40 C, the 58-year-old and his colleagues have to wear quilted coats and pants in the caves to keep warm. Arthritis is a hazard for some.

They also need to keep their hands raised for hours, exerting strength, but not shaking when their muscles tire, a challenge that can be very energy consuming, his colleague Li Lingzhi, 36, says.

However, for Li Bo, it's often not until he steps out of the caves after several immersive hours that he starts to feel the exhaustion.

Li Lingzhi says Li Bo shares all he knows without reserve.

He says, he's always impressed by the awe displayed by the older generations toward the cultural heritage, and the more comprehensive point of view they have of the tasks.

Li Bo admits that compared to "green hands", an experienced restorer spends less time forming up a solution, and meanwhile, they take a greater number of factors into consideration.

He has strong support behind him, including his father Li Yunhe, the academy's first full-time cultural heritage restorer, who has been dedicated to the cause since 1956.

Li Yunhe once removed a mural, completely intact, from a corridor in Cave 220 of Mogao Caves, to expose an older mural hidden underneath. He then placed the murals side by side so that scholars and tourists can see them both.

Li Bo grew up watching his father restore the murals and painted sculptures, taking in all he saw and heard. In 1983, he joined the academy, and was involved in the archaeological mapping of the caves before formally taking up the preservation and restoration of these cultural relics in 1990.

"I felt it was my duty to take care of my father while learning something at the same time, and he is very strict with me," Li Bo says.

Apart from restoring murals and painted sculptures at Gansu's cave temples, the father and son also attended preservation projects in Qinghai, Shanxi and Zhejiang provinces, as well as Tibet and Xinjiang Uygur autonomous regions, among others.

Thanks to rich experiences garnered by the Dunhuang Academy in the past decades, conservators there have supported preservation projects of earthen heritage sites and murals in 20 provincial-level administrative regions across the country. They have also contributed solutions to similar sites in other countries like Kyrgyzstan and Myanmar, according to Guo Qinglin, deputy director of the academy who is in charge of cultural heritage conservation.