Turkish foreign policy unlikely to change

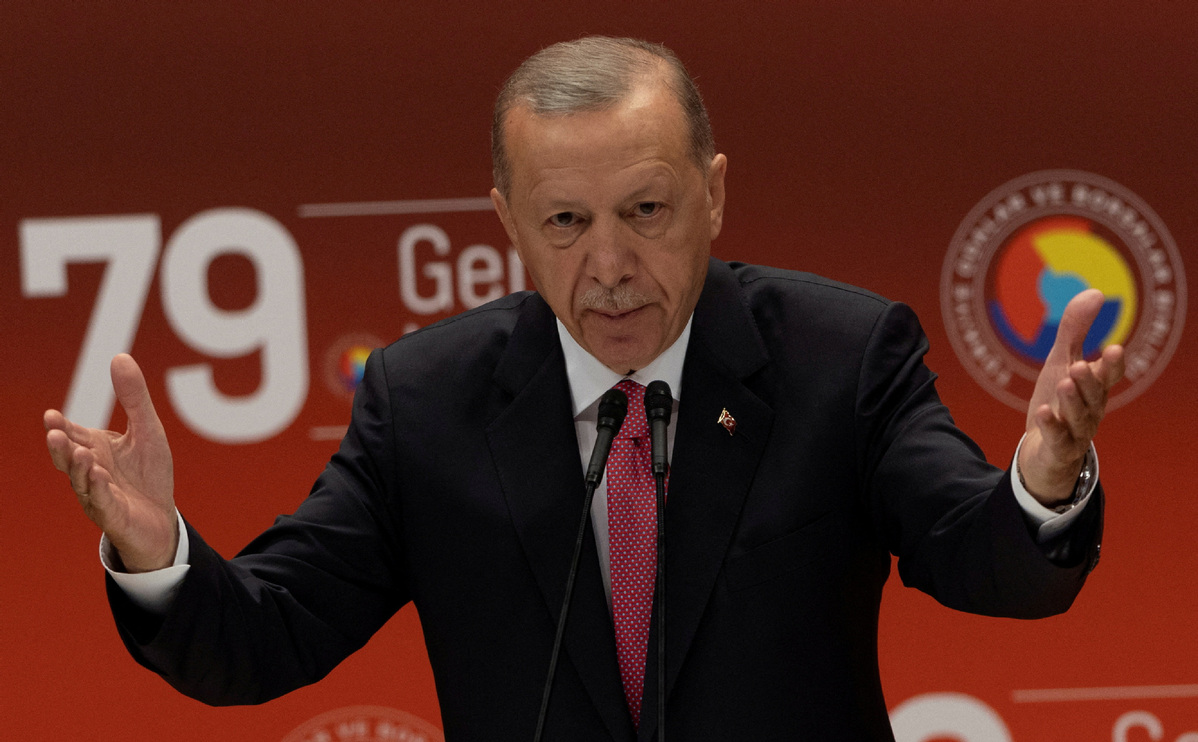

The victory of incumbent President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in the Turkish presidential runoff met societal needs at home and points to stable policies in foreign relations.

Erdogan, of the Justice and Development Party, also known as the AK Party, aligned his interests with Turkiye's strongest nationalist party, the Nationalist Movement Party, which got 10 percent of the votes in the May 14 parliamentary elections.

He also aligned with Sinan Ogan, who had won 5.3 percent of the votes in the first round of presidential elections on May 14.

Erdogan was reelected with almost 28 million votes of the 54 million total, or around 52 percent, while opposition leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu of the Republican People's Party, received almost 48 percent of the votes, amounting to nearly 26 million in total. Considering most opposition members thought that Kilicdaroglu was going to be elected with 54 percent of the votes in the first round, it ended as quite a significant defeat.

Erdogan's other small partners included the New Welfare Party, Great Unity Party, Democratic Left and Free Cause Party — each of which had picked up a small percentage of the parliamentary vote.

Kilicdaroglu of the CHP officially collaborated with the Good Party, which won 9 percent of parliamentary votes along with smaller parties — Felicity Party, Democrat Party, Democracy and Progress Party and Future Party.

Kilicdaroglu also unofficially received support from the Party of Greens and the Left Future, the Turkish Communist Party and other small partners. The Victory Party also backed Kilicdaroglu, not Erdogan, in the runoff stage, despite supporting Ogan in the first round.

Erdogan's coalition only inducted the New Welfare Party and the Free Cause Party, which hold contradictory views on social and women's rights as well as issues such as gambling and the death penalty.

Kilicdaroglu's coalition included former compatriots of Erdogan's — his former prime minister Ahmet Davutoglu of the Future Party and former deputy prime minister Ali Babacan of the Democracy and Progress Party.

The rivalry between Davutoglu and Babacan is deep, and it almost derailed their support for Kilicdaroglu. Their parties only backed him two months before the presidential election.

In March, at the outset of the presidential campaign, Meral Aksener — the leader of the Good Party — left the opposition coalition. She rejoined the six-party alliance days later but the damage was done.

Since then, the opposition did not stand together to fight the election. Aksener was persuaded to rejoin on the condition that Istanbul Mayor Ekrem Imamoglu and Ankara Mayor Mansur Yavas would be vice-presidents, but this hurt the other partner parties, which had their eyes on these roles.

Why did the opposition expect such a victory when most of the polls portrayed a very close call for Erdogan and Kilicdaroglu, even suggesting a runoff?

The opposition seems to have succumbed to the idea that economics was more than enough to ensure a landslide in elections. However, the Turkish political sphere is much more complex than economic parameters such as inflation and interest rates.

Most of the opposition was heartbroken and angry, since they could not snatch a first election victory in over two decades. Some opposition members channeled this anger toward Kilicdaroglu, asking him to resign immediately. Others simply insulted Erdogan's voters and claimed that they were illiterate, ignorant and blind.

However, a very small section of the opposition asked the right question, about what they did wrong.

One of the opposition's main mistakes was relying on February's deadly earthquake and economics to defeat Erdogan. Second, no clear-cut political and economic strategies were made public to solve the issues that Turkish citizens are facing. People were not convinced that the opposition would be able to attract capital and reduce the economic pressure of daily life.

There are very important insights to be generated from this election, for a better understanding of Turkish society.

First, it sincerely cares about nationalism and security, both internally and externally.

Second, voters do not actually want to see a party that has embedded relations with terrorist organizations such as the PKK and YPG.

Third, Turkish society wants to protect its conservative fabric and does not have an open-door policy for LGBT demands.

Fourth, the individuals do not want to return to a Turkiye where the state asks for funding from international fund providers such as the International Monetary Fund.

Fifth, and maybe most important, society demands a very strong character to represent them in the international arena.

All these causes and conditions have been the main course of action for the People's Alliance that supported Erdogan, and it seems to have paid off very efficiently.

Regarding international affairs, there is not going to be a drastic change in Turkish foreign policy, as Erdogan remains president. However, Turkiye will be dealing with severe economic pressure from the West as payback for this victory. That is almost certain.

The author is a research assistant at the Middle East Institute of Sakarya University in Turkiye. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.