In new world, Britannia shows the way

Comments Print Mail Large Medium Small

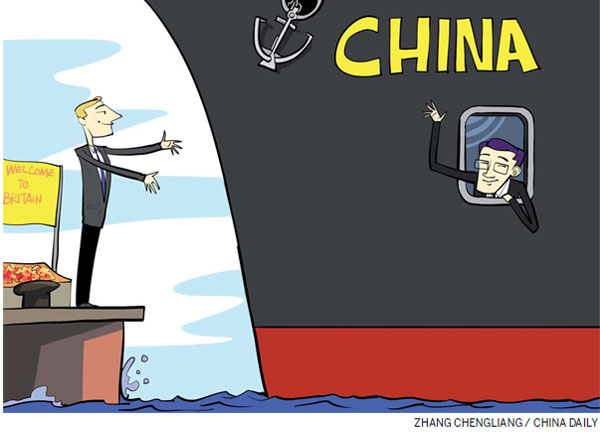

UK's welcoming of premier li reflects constructive way of handling country's inevitable rise

Premier Li Keqiang's recent visit to London, accompanied by a large group of Chinese business leaders, has produced several large contracts for direct Chinese investment into British infrastructure, including the British nuclear power industry, a sector famously sensitive to foreign involvement.

China's participation as a major investor has raised questions about the United Kingdom's relationship with China. "We wouldn't be bowing to the Chinese unless we needed their money," the British media say. But China's economic and social development has reached the point where closer engagement with the rest of the world has become inevitable. How will this huge, potentially highly beneficial change develop in a peaceful and constructive way, if major Western countries refuse to accept it?

In May, I participated in a meeting in Beijing with a delegation sent by a leading US think tank to study the current Chinese situation. One of the subjects we discussed was a recent report by the World Bank that the Chinese economy would be the largest in the world next year, outstripping the US economy in purchasing power terms during the course of the current year.

How would the United States deal with not being the largest single economic power, with its implication of a loss of geopolitical power and influence? The response from the US delegation to this question was guarded and formal. One person said he didn't mind China being larger than the US; another said the issue of size was of more concern to the Chinese than to the Americans. We moved onto other topics.

But toward the end of the meeting, when we were talking about the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a US-led multilateral trade agreement among Pacific countries including Japan but excluding China, a member of the US delegation leaned across the table and asked me: "Is the containment working?"

He wanted to know how the Chinese were thinking about US efforts to limit China's increase in power and influence by coordinating opposition to China around the eastern Pacific. I replied that such a policy of containment could not work beyond the immediate future because China would insist on being treated as an equal by the US. I said Washington would have to find another way, apart from containment, to think about and deal with Beijing.

A shift in global power has been talked about since the British banking economist Jim O'Neill coined the

expression BRIC in the early millennium to describe the four countries (Brazil, China, India and Russia) outside the G7 whose economic growth and population would bring increasing power and influence. Today, more than a decade later, the much-discussed and expected global power shift is becoming a pressing reality.

The developed world has certainly woken up to the trade possibilities in the emerging world. The capital goods manufacturers of Germany and Japan have been major beneficiaries of strong demand for machinery of all kinds from the emerging world.

When the financial crisis struck in September 2008, the financially stricken developed world was forced to call upon the emerging world's financial resources to restore confidence and stability in the world system. For a few months, the G20, which includes the BRIC countries and others from the emerging world as well as the original G7, did play a central role in global financial and political affairs.

Six years later, the importance of the emerging world in global affairs has waned. The US Congress earlier this year refused to ratify the IMF board decision giving the emerging countries, led by China, more voting power. And recently, MSCI, the organization that supervises the widely-followed and all-important index weightings in global stock indices, announced that Chinese mainland markets would not be included in the global emerging market index.

Against this background of refusal by the West, particularly the US, to accept the new world order in which China is prominent, Li Keqiang's visit to the UK in June stands out as a splendid exception and example. When British Prime Minister David Cameron said in a public speech during the visit that China's emergence was one of the major global developments of this century, he was only stating the obvious.

With nearly one-fifth of the world's population, a huge, strategically important landmass, the world's second-largest economy, more poor people than any country except India and one of the world's most influential cultures, the emergence of China into the global economic and geopolitical system must be inevitable, and a great event. Whether this event brings new global growth and prosperity and a better world, or an increase in tension resulting in catastrophe does not depend just on China. Its major partners have to come to its party as well.

Li's visit to Windsor Castle to meet the British queen marks the formal welcome of China into British society. As a consequence of negotiations finalized during his trip, China will invest in some core British infrastructure projects, including the north-south British high-speed rail link, the long hoped for expansion of London's main airport, and the new nuclear power facility at Hinkley Point.

Li underlined the importance of Britain as a destination for Chinese students when he announced government scholarships for 10,000 students to study in Britain over the next five years. China Construction Bank was appointed as the London clearing bank for Chinese currency trading, strengthening London's position as the renminbi European trading and settlement center against Frankfurt, Luxembourg and Paris. The emergence of China's currency as a global reserve currency within the next few years, which is inevitable, acts as a flag-carrier for steadily increasing Chinese involvement in every aspect of life around the world, including in Western countries. This global expansion has already happened via the export of Chinese-made products, but as most of these came from foreign-owned factories in China, they carried a foreign label. Now the label is Chinese.

The UK has been formed over several thousand years by a series of foreign incursions. For 300 years, its kings spoke only French. Later, the first king in the present dynasty, George I, the present queen's ancestor, was invited from Hanover to take the crown of England. He spoke only German. After World War II, as Britain's Empire faded, millions of immigrants from Asia, Africa and the Caribbean flooded into Britain, the country they called their home. Many spoke no English. Today Bradford, a large city in northern English, is 25 percent Asian.

The result of multiple foreign incursions into Britain, over hundreds of years, is that the United Kingdom is ready to accept new cultures and open up to different ways of looking at things. It's natural that the UK, rather than France, Germany or even the US, should be the leader among the G7 countries in bringing China into the inner circle of influential countries

Li's London visit has major significance for China's future role as a world power whose culture and economy will stretch into every corner of global affairs. Britain has changed the rules by welcoming this development, not trying to stop it. It's a step forward that will be studied carefully by other Western powers, and eventually imitated by them.

The author is a visiting professor at Guanghua School of Management, Peking University. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

(China Daily Africa Weekly?06/27/2014 page10)