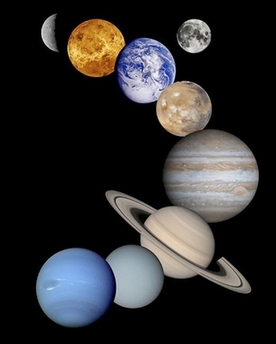

This 2001 NASA montage

of planetary images was taken by spacecraft managed by the Jet Propulsion

Laboratory in Pasadena, California. From top to bottom: images of Mercury,

Venus, Earth (and Moon), Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. The

solar system may soon be home to a dozen planets, with three new additions

to the club and more to come, if astronomers meeting in the Czech capital

approve a new planetary definition, the conference organizer has said.

[AFP] |

Pasadena, California - Few planet hunters

stand to gain as much as Michael Brown if our solar system balloons to 12

planets under a new definition. He's spotted more than a dozen objects that

might qualify as planets.

So why is he upset?

"When I was a kid, planets were special," he said. "This definition takes the

magic out of the solar system."

It was Brown's discovery of an icy rock bigger than Pluto that helped lead

astronomers to rethink their definition of what a planet is. But Brown doesn't

think his discovery, or even Pluto, which was spotted in 1930, should qualify as

true planets.

On his website, the California Institute of Technology astronomer muses about

why Pluto has kept its title for so long: "I think that astronomers are as

sentimental as the rest of the world and couldn't stomach removing Pluto.

Probably they also couldn't stomach the criticism that would follow."

Last week, a high-ranking panel from the International Astronomical Union

proposed that the solar system be expanded to 12 planets from the current nine,

the first attempt at creating a scientific definition for planets.

Under the proposed definition, an object is a planet if it is at least 500

miles in diameter, orbits the sun, and has a mass at least about one-12,000th

that of Earth.

Pluto would keep its planethood while three other bodies would be added,

including Pluto's moon Charon, the asteroid Ceres and Brown's object 2003 UB313,

which he nicknamed Xena.

Brown said the proposal, that a planet is basically anything round orbiting

the sun, is too broad and amounts to "No Ice Ball Left Behind," cheapening the

solar system.

He worries that by the time his daughter, Lilah, now 13 months, is old enough

to memorize the planets, there could be hundreds.

In scientific circles, Brown is a star known for his outspokenness. But vocal

as he is, he is not a member of the professional astronomers' group and will be

shut out of Thursday's vote on the proposal.

"I feel like an outsider. It's an odd situation," said the 41-year-old, who

was named one of Time Magazine's 100 Influential People of 2006.

Still, he is the one whose discovery helped initiate the process.

"Mike deserves a lot of credit for bringing this question to the forefront,"

said Alan Boss, an astrophysicist at the Carnegie Institution in Washington,

D.C.

"We don't agree on how planets should be defined, but I certainly respect him

very much," said Gibor Basri, a University of California, Berkeley astronomer

who has known Brown since he was a graduate student. Basri belongs to the camp

that believes Pluto is a true planet.

Brown grew up in Huntsville, Ala., nicknamed "Rocket City" because it is the

home of NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center. As a kid, he would hear rocket test

firings and knew early on that he wanted to be an astronomer.

He would nag his grandparents to take him to the U.S. Space & Rocket

Center and even asked his mother for a subscription to Astronomy magazine for

Christmas. As a teenager, Brown was glued to the Voyager missions to Jupiter and

Saturn, but never imagined a career as a planet hunter.

"I loved the planets, but I never thought I wanted to go find a new one," he

said. "For a long time, everyone thought Pluto was it. There's nothing further

out there."

His perception changed while he was a Ph.D. student at Berkeley, where his

colleagues made the first discoveries of icy objects besides Pluto in the Kuiper

Belt, the region beyond Neptune containing thousands of comets and objects

called planetary bodies.

Brown figured there must be something larger than Pluto in the frozen fringes

of the solar system. He joined Caltech's faculty in 1997 and quickly gained a

reputation as the man who had a knack for spotting objects with a telescope.

Brown spotted Xena last year after re-examining images taken in 2003. He

noticed something strange, Xena was too big and too bright. He calculated its

size from its brightness and had a eureka moment: Xena was larger than Pluto.

The first thing Brown did, he recalls, was phone his wife, who replied:

"That's nice, honey. Can you pick up some milk on your way home?"

By Brown's own count, 14 of his discoveries besides Xena are in the running

for planethood. That could make Brown the most prolific planet hunter.

But he supports an eight-planet solar system, although he wouldn't mind if

Xena was added as the 10th planet.

"When people finally realize the number of planets is going to be much

bigger, they'll shake their heads and say 'Astronomers are crazy.'" Brown said.