Time to read even the fine print

Traveling in China, I found many massage parlors in the streets but few bookstores. The average time a person in China spends reading a book is 15 minutes a day, one-tenth of that spent by an average Japanese.

Above is a quotation from Japanese author Ohmae Kenichi's book, Low-Intelligence Society. His summary of Chinese people's reading habits was corroborated by the 10th National Reading Survey released last week. More than half of the respondents to the survey admitted that they read very little. Statistics show that an average Chinese reads only 4.39 printed books a year, even though the national reading rate increased by 1 percentage point in 2012. Whereas people in the Republic of Korea and Japan read an average of 11 and 40 books a year.

Public zeal for reading should have risen in this age of knowledge explosion but the scene today is worse than the 1980s, and it's frustrating to read that half the Chinese population has quit reading.

Some have put the blame on digital reading, which many people prefer to traditional books. Digital reading, according to the survey, on computer screens, mobile phones and e-readers in 2012 may have increased by 1.7 percent year-on-year to 40.3 percent but it has not offset the drop in the average reading time of Chinese people. The blame should thus be on the changing reading habits and patterns of Chinese people rather than the reading medium.

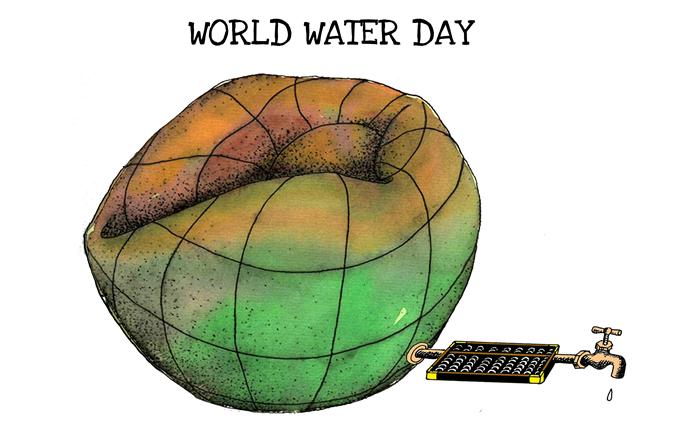

How do we gather information today and what do we read? E-mails that could be deleted in a flash, micro blogs of 140 words at most, and messages on mobile phones and instant messengers on computer screens. A day in new media times seems to be shorter than it really is, which not only requires us to do things in less time, but also leads to fragmentation of information and way of thinking.

In the age of weibo, it is common for people to read postings of not more than 140 words to check the latest happenings, which many working people and students start their day with. There is a surfeit of convenient, brief but "illogical" contents and we have fallen prey to them, subconsciously or otherwise.

Fragmented writing, a product of the fast-paced life in the West, is supposed to give maximum information to readers in the minimum time. However, the emergence of fragmented reading materials has not driven Western readers away from printed books.

It seems Chinese accord less priority to reading and don't think that highly about acquiring knowledge (or gathering information) the traditional way. As long as the reading materials offer people what they like or need, they don't mind reading even fragmented materials with limited and casual contents. In fact, fragmented reading materials even offer people not interested in reading books an excellent chance to portray themselves as knowledgeable by using their fragmentary knowledge in conversations as if they knew all.

The essence of reading in the real sense, irrespective of the medium, is to cultivate the competence of understanding abstract thoughts and discussing topics of serious spirit. Reading fragmented materials can never give readers the spiritual joy or feeling of exploring the world through authors' words because of the disconnect among connotations, rationale and logic.

Fortunately, about 70 percent of the respondents to the survey, aged between 18 and 70, said they realized that they had alienated themselves from quality reading and hoped relevant local government departments would organize reading activities, and 73.2 percent of rural residents welcomed such activities with greater enthusiasm than their urban counterparts.

A handful of such activities such as reading seasons or festivals have already been held in big cities like Beijing and Shanghai, and hopefully they will cover a wider range in second and third-tier cities as well as rural areas to meet local residents' reading needs.

To genuinely help people develop a good reading habit and fan their passion for quality reading, the government and relevant social sectors should not only encourage the publishing of books on a wider variety of subjects, but also make efforts at both the central and local levels to promote healthy reading habits.

Some social funds have been set up to draw people toward books and some publishers have gradually begun introducing new patterns and fashions to promote reading. These efforts, though appreciated, are far from enough.

Whether or not people regain their healthy reading habits depends on their willingness. Even though pragmatism and pursuit of success are not essentially bad things, it is still important to cater to our spiritual needs through books in the hustle and bustle of today's society.

The author is a reporter with China Daily.

(China Daily 04/26/2013 page9)