Hoisted by their own petard

Nations that have chosen to side with the US against China have been left high and dry as it has failed to keep its word

Most Asian countries have sought to maintain their strategic autonomy and avoid taking sides in the competition between China and the United States. However, under pressure from the US, some nations have made notable shifts in their China policies, regional strategies and approaches to handling sensitive issues.

In Northeast Asia, Japan's policy toward China has increasingly leaned toward "aligning with the US to contain China". Militarily, Japan has significantly expanded its defense budget; economically, it is pushing for "de-risking" from China; and in terms of security, it actively supports NATO's expansion into the Asia-Pacific region. Japan's ambition to leverage the US to gain dominance over Asian affairs is becoming more evident in its playing along with the US in stirring tensions in the East China Sea, the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait.

The Republic of Korea's China policy under the current administration has shown a clear tilt toward aligning with the US and distancing from China. Seoul has actively bolstered the US-ROK alliance and advanced trilateral cooperation with Washington and Tokyo. It has adopted a hardline stance toward China on several key issues, including joining the US-led "Chip 4 Alliance", participating in the "Indo-Pacific" Economic Framework for Prosperity, and publicly aligning with the US on matters related to the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea.

In Southeast Asia, some countries have exhibited growing tendencies to "align with the US to counter China", with the Philippines being particularly prominent. The Ferdinand Marcos Jr. administration not only reopened and expanded US access to military bases in the country but also actively supported multilateral security frameworks, such as the US-Japan-Philippines and US-Philippines-Australia partnerships. As external powers such as the US and Japan increase their involvement in the South China Sea, the Philippines has adopted a much harder line on its maritime dispute with China.

In South Asia, India has drawn closer to the US strategically. The Narendra Modi administration has taken a hard stance on issues such as border disputes and economic frictions with China, continuously provoking tensions. Regionally, India has embraced the Quad (the US, Japan, Australia and India), while distancing itself from the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and BRICS mechanisms. India hopes to leverage US and Western support to replace China as a global manufacturing hub and achieve its goal of rising as a major power.

Clearly, these nations' decisions to align with the US aim to reap four strategic "dividends". First, on security, they hope cooperation with the US will bolster their own defense assurances. Second, economically, they anticipate gaining trade, investment and technological cooperation benefits from the US. Third, geopolitically, they aim to counterbalance China's influence with US support. Last, internationally, they seek to elevate their status through their alignment with the US.

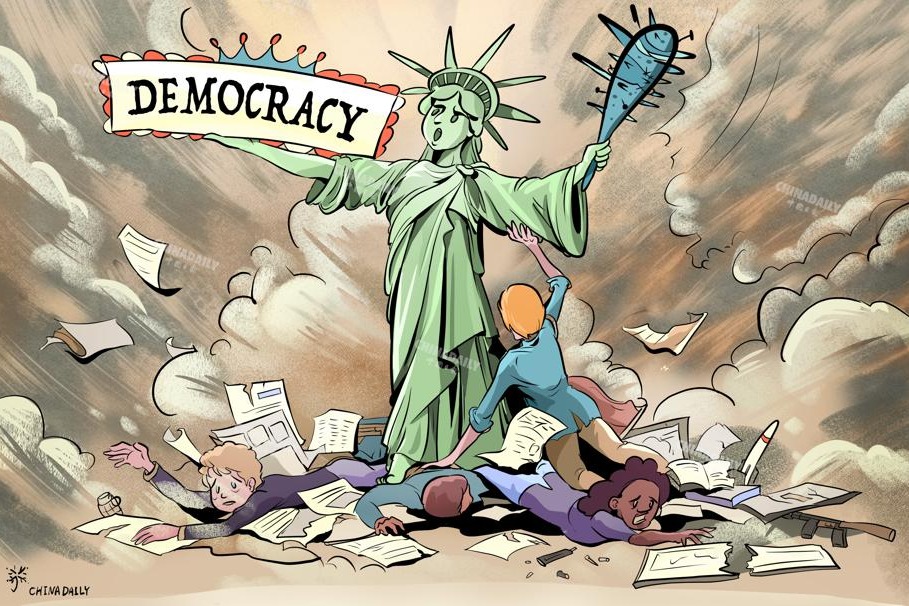

However, the reality has not unfolded as they expected. Countries choosing to side with the US have paid a steep price for doing so. On security, they are pushed to the forefront of confrontation with China, facing increased risks of conflict and military friction. Economically, they have failed to reap the anticipated dividends, while deteriorating relations with China have caused them to miss opportunities for deeper cooperation. Politically, their diplomatic autonomy has been significantly weakened, leaving little room for policy adjustments and placing them in an increasingly passive position amid China-US competition.

Washington has made numerous promises of financial aid, market access and industrial relocation opportunities to get countries to side with it. However, these promises have largely remained hollow.

For example, while the "Indo-Pacific" Economic Framework for Prosperity has been highly publicized, it lacks substantive measures for market access and trade benefits, falling far short of what the member countries hoped for. The CHIPS Act, ostensibly aimed at building a "secure semiconductor supply chain" with allies, has instead prioritized "America First".Most subsidies have gone to US-based companies, while foreign companies, including those in Japan and the ROK, face strict restrictions when applying for funds.

The "side-choosing" countries have also overestimated their role and influence in China-US competition. They imagined they could "sit on top of the mountain to watch the tigers fight", reaping benefits while the US took the lead in confronting China.

In reality, when conflict risks with China have escalated, the US often "hit the brake", seeking engagement with China to manage risks and prevent escalation. For "side-choosing" countries, however, the US continues to "press the accelerator", pushing them directly to the forefront of confrontation with China — whether through upgrading military alliances with Japan and the Philippines or reinforcing trilateral cooperation with the ROK.

As a result, these countries find themselves not in control of the situation but deeply bound to the US, becoming "proxy conflict actors" in the great power rivalry. More critically, as geopolitical tensions persist, their strategic expectations remain unmet, while Asia's economic cooperation and security environment are dragged into a "high-risk zone". Through swift and precise responses across economic, diplomatic, legal and law enforcement domains, China has significantly raised the strategic costs of pursuing anti-China policies.

What lessons can Asian nations draw from this?

First, in the face of China-US competition, Asian nations should avoid taking sides. Rather than trying to speculate on who will win, they should focus on maintaining their strategic autonomy and balancing relationships to preserve their policy flexibility and diplomatic independence.

Second, Asian countries must reassess US motives for intervening in regional conflicts. Whether in the Taiwan Strait, the South China Sea or the Korean Peninsula, Washington's involvement under the pretext of "peace and stability" has often escalated tensions and created regional divisions. Asian nations must remain highly vigilant.

Third, when addressing disputes with China, Asian nations should prioritize risk management and avoid escalation. Recent efforts by China and India to cool border tensions demonstrate that dialogue and negotiation remain the most effective means for resolving differences and frictions.

Fourth, to mitigate the risks of a new Cold War, Asian countries should influence the trajectory of China-US competition through cooperation and coordination. By building communication platforms, they can promote cooperation and reduce confrontation. Advancing regional integration and maintaining an open and inclusive order will showcase regional unity and strategic autonomy, adding "guardrails "to this competition.

The author is an associate research fellow at the Institute of World Economics and Politics at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. The author contributed this article to China Watch, a think tank powered by China Daily.

Contact the editor at editor@chinawatch.cn.