Have the 'samba boys' lost their rhythm?

Despite its five World Cups and firmament of stars, Brazil has fallen out of step with its reputation as 'the land of soccer'

SAO PAULO — With its famed "jogo bonito", iconic stars and record five World Cup titles, Brazil has long been known as the "land of soccer".But is it still?

The country of Pele, Garrincha and Ronaldinho, which once wowed the world with its "samba" style, has not won the World Cup since 2002.Nor has it produced a Ballon d'Or winner since Kaka in 2007.

With the "Selecao" currently struggling to book its place at the 2026 World Cup, many in Brazil and beyond wonder why.

"We're at a low point. We used to have more top-quality athletes," the late Pele's eldest son, Edinho, told reporters recently.

Even Brazil's President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva has joined the national soul-searching, admitting Brazil "doesn't play the greatest football in the world anymore".

So what happened?

Disappearing pitches

One answer could be the decline of street soccer, where some of Brazil's all-time greats started out, such as Rivellino, Zico and Romario.

"Nobody plays in the street anymore. You don't hear stories about that kick that broke somebody's window," says amateur player Lauro Nascimento, his jersey stained with orange mud after playing on one of the few dirt pitches left on Sao Paulo's north side.

Nascimento, a 52-year-old finance professional who plays for local side Aurora, broke several toes playing soccer barefoot as a boy.

Today, the district of Vila Aurora is covered in a concrete sprawl. Two buildings stand on what was once open pasture that was used as a soccer pitch.

"Any open space used to be enough for kids to get their start in soccer. Now, it's seen as prime development real estate," says sports historian Aira Bonfim.

Nascimento and his friends pay $160 a month to rent the battered scrap of land where they play matches, but that kind of money is a barrier for working class families.

To access a pitch today, poor kids in Brazil often depend on school, social programs or soccer academies.

Many of those pitches are synthetic, a surface some say doesn't develop players' technique as well as the rough, rocky fields of yesteryear.

Also, only one in five academies is free, according to a 2021 study.

Too 'Mechanical'

The decline in time spent playing the sport has had "a giant impact on our soccer", says researcher Euler Victor.

"We have a huge number of Brazilians playing in Europe, but very few stars."

Brazil's latest great hope, Neymar, shone at Barcelona, but struggled to lead the national team to championships in a career bogged down by controversy and injury.

Brazilians now have their hopes pinned on 23-year-old Vinicius Junior and young phenomenon Endrick, who is set to join Vinicius at Real Madrid when he turns 18 in July.

Brazil is still the world's top exporter of footballers, but they are bringing in less money.

According to FIFA figures, clubs paid $935.3 million in transfer fees for 2,375 Brazilian players last year, down nearly 20 percent from 2018, when the number of players was smaller — 1,753.

Part of the drop is because teams are paying less to hire free agents and younger players.

But, there is also a shortage of standout stars.

"Our technique has suffered," says Victor Hugo da Silva, a coach at Flamengo's youth academy in Sao Goncalo, outside Rio de Janeiro.

"The playing style changed, and that ended up taking away some of our creativity. Our soccer used to be so joyful. Now it's become more mechanical."

On a synthetic pitch, he trains seven- to 10-year-olds dreaming of following in the footsteps of Vinicius, the academy's most famous graduate.

The next generation still has soccer in its veins, but has "difficulties "with training, a problem Da Silva attributes to their sedentary lifestyles and "addiction" to screens.

Brazil, with a population of 203 million, has more cell phones than people. More than one-third of children aged five to 19 are overweight or obese, according to data from the World Obesity Atlas.

Robson Zimerman, a talent scout for Sao Paulo club Corinthians, says that emerging players today face tougher conditions, including the necessity to play multiple positions and outsized expectations from family and the media.

"Before, they just had to worry about playing soccer," he says.

But Leila Pereira, president of crosstown rivals Palmeiras, the reigning league champion, insists Brazil will never stop being the country of soccer.

Brazilian teams have claimed the past five Copa Libertadores titles, with Palmeiras claiming two of those.

The club is a cradle for talents like Endrick — whose sale to Real Madrid brought in a reported $65 million with bonuses — as well as rising prospects Estevao Willian and Luis Guilherme.

"I disagree with those who think (Brazilian players) have lost quality. Look at the astronomical sums they bring in," says Pereira.

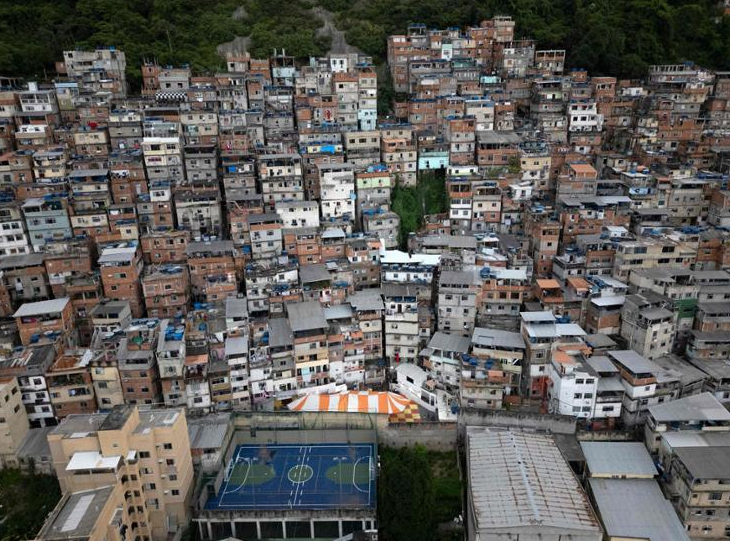

Favela party

For many people, Pereira, one of Brazil's wealthiest people, is the face of a new brand of Brazilian soccer — more like Europe's, with lavish salaries, by South American standards, and expensive ticket prices.

"With the absurd salaries they pay the players, clubs have to raise ticket prices, which excludes fans like me," says Flamengo supporter David Santos.

In 2019, he founded a fan club for Flamengo die-hards like himself from the impoverished favelas.

From atop the hillside slum that overlooks the trendy beach neighborhoods of Copacabana and Ipanema, they recreate the ambiance of the Maracana on match days, decorating an old pitch with flags, grilling barbecue and belting out chants as the match plays on a giant screen.

"The 'country of soccer' thing — we're losing that," says one attendee, 38-year-old Vasco fan Pablo Igor.

"Soccer is what you see here. It's a game of the people, but street kids — like I was — don't have access to it anymore."

AFP

Most Popular

- Paris Paralympics ticket sales exceed 2.3 million

- US NBA team visit Shanghai

- Zheng Qinwen into US Open quarter-final

- Serena returns to US Open — as a fan

- Does Djokovic defeat spell the end of golden generation's era of dominance?

- Sinner stakes his claim as Open favorite