Bamboo slips reveal an ancient world

Details of official's career help researchers build a picture of life 2,000 years ago, Fang Aiqing and Liu Kun report.

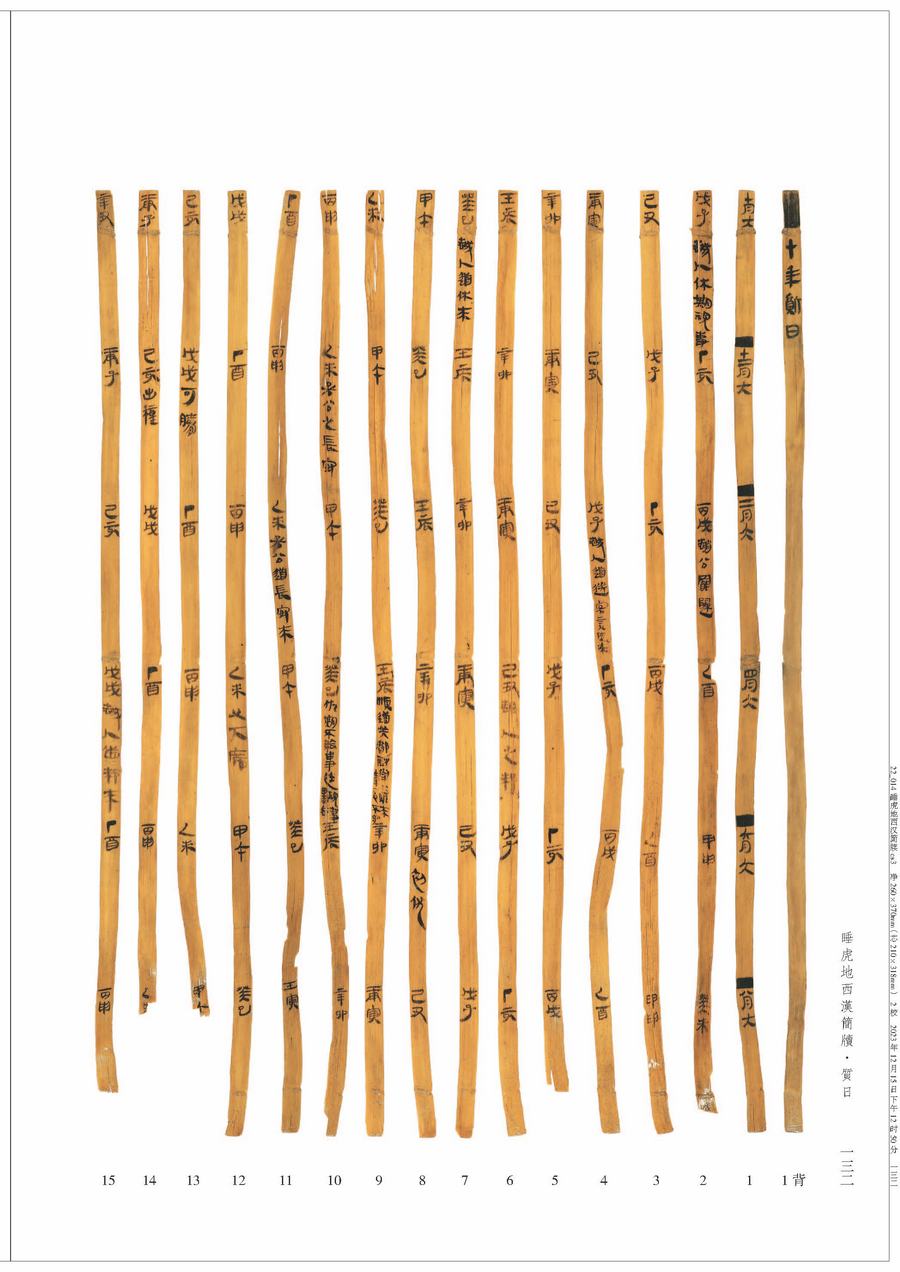

More than 2,000 years ago, a low-ranking official recorded details of his work and life spanning 14 years on bamboo slips. These journals were buried in his tomb in what is today, Shuihudi village, Yunmeng county in Central China's Hubei province. They were meant to accompany him into the afterlife.

An accidental discovery and the resulting excavation in 2006 brought these relics to light. Years of study into these records has formed a vivid impression of this Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24) official, Yueren, as well as increased knowledge of the calendar system, grassroots governance and household tax at the time.

For example, Yueren had beautiful handwriting. He was literate — an essential requirement for grassroots officials — and seemed particularly good at accounting.

He had story books buried with him that could possibly have been his favorites, as well as two volumes of law codes. His work largely involved measuring land, checking the registered population and reporting on economic and social data. He had to travel a lot for work.

From 170 to 157 BC, during the reign of Emperor Wendi of the Western Han Dynasty, Yueren wrote zhiri, a diary form that's similar to today's calendar, marked with the dates and a small space to fill in daily schedules. One volume of the diary covers the time span of a year.

This form of record-keeping was once popular during the Qin (221-206 BC) and Western Han dynasties but is rare in literature passed down through history, according to Chen Wei, director of Wuhan University's Center of Bamboo and Silk Manuscripts.

It is via this type of unearthed bamboo slip that archaeologists and historians are able to learn about zhiri, which in the old days, was also used as a reference in assessing the performance of officials, he adds.