HK artisan values allure of traditional instrument

HONG KONG — Choi Chang-sau still vividly remembers his first encounter with his master. Over 70 years ago, his father, who ran a musical instrument shop, entrusted him with returning a guqin, a plucked seven-stringed musical instrument, that he had repaired, to its owner. The recipient was a gentleman named Xu Wenjing, who had settled in Hong Kong in search of treatment for an eye ailment.

Little did Choi know that this encounter would ignite a lifelong love affair with the guqin, an instrument that has resonated through Chinese history for over three millennia.

Xu was a virtuoso in guqin performance, the interpretation of ancient scores, and the art of making the instrument, and Choi found himself irresistibly drawn to its allure. In displays of youthful rebellion, he occasionally skipped school to seek the wisdom of his newfound mentor. Through a stroke of fate and the recommendation of a renowned guqin artist, Choi was eventually accepted as Xu's apprentice, embarking on a transformative journey that would shape his destiny.

As Xu's eyesight faded, his hands became the vessel through which the ancient secrets of the guqin were transmitted. Choi learned to decipher the intricate nuances of the instrument's curved surface with his fingertips, and honed his ability to discern the subtle characteristics of the wood, its thickness, imperfections, and tonal qualities, simply by listening.

The guqin is one of the earliest plucked instruments in China. Among the four arts revered by ancient scholars — qin (the guqin), qi (the game of Go), shu (calligraphy), and hua (painting) — the guqin holds the esteemed position of being the first.

Xu was an adept of the Zhe School (named after the region in Zhejiang), a distinguished lineage emerged during the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279), and he inherited the venerable tradition. As its torchbearer, Choi then assumed the weighty responsibility of preserving its cultural essence for future generations.

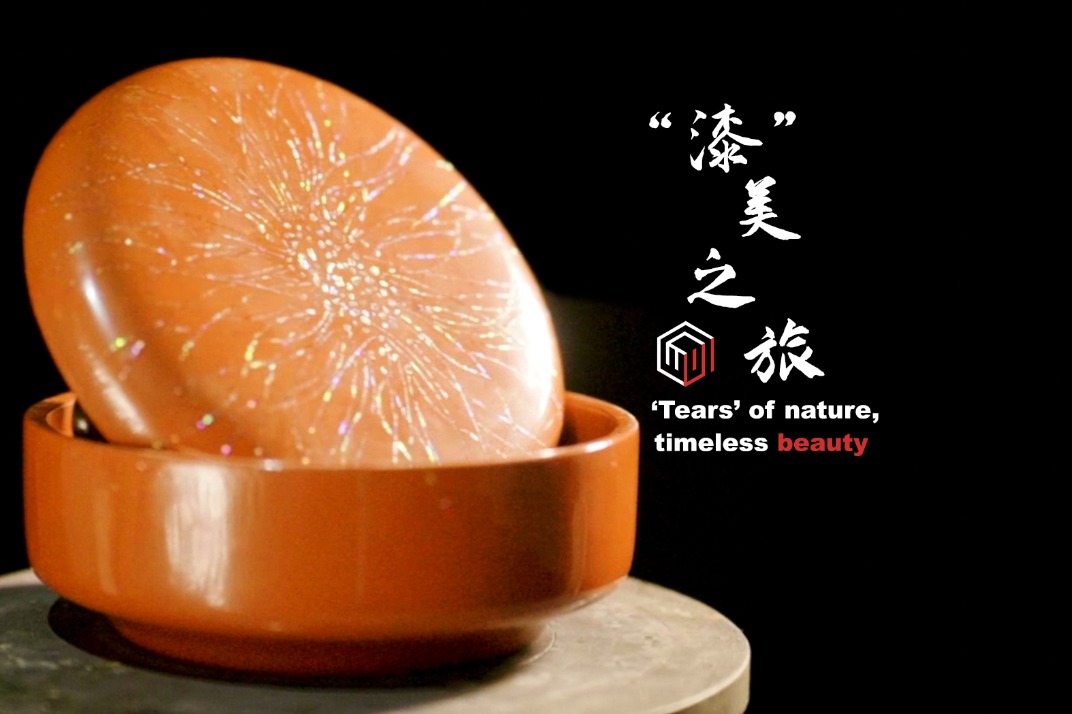

From selecting the finest wood to shaping the instrument, carving the soundboard, hollowing the resonance chamber, polishing, lacquering and stringing, the process of making a guqin is undertaken by a single maker. This is a distinctive feature of Choi's craftsmanship.

The completion of a single guqin requires an average of 200 hours of meticulous work. To graduate, Choi's apprentices must finish making three instruments and their "graduation certificate" takes the form of a brown apron emblazoned with the words "Choi Chang-sau Qin Making Society".

This society is Choi's institution for teaching and conducting research into the guqin. Located on the fifth floor of a building in Shek Kip Mei in Hong Kong's western Kowloon district, it consists of a reception room and two work spaces. The tools and wood are mostly provided by Choi.

Much of the wood used here is over a century old. It comes from a wide range of sources, including old beams, pillars, doors and wooden furniture salvaged from demolished houses, and even fenders from the docks or old bridge planks purchased from San Francisco.

Since it is the most crucial component, knowing how to find quality wood is one of the most important aspects of heritage preservation. Despite already having a substantial supply of century-old timber, whenever Choi hears of an old building being dismantled, he becomes a treasure hunter.

While wood is essential to guqin making, having woodworking experience is not a prerequisite to becoming one of Choi's students. The first requirement is to be able to play the guqin.

He believes that people who cannot play will struggle to discern quality and the key to preserving ancient methods lies in having a deep understanding of music, he says.

The physical structure of the guqin was formalized during the Wei (220-265) and Jin (265-420) dynasties, around 1,800 years ago. Even today, surviving Tang Dynasty (618-907) melodies can be faithfully reproduced, with the musical notations transcending the passage of millennia.

Since the 1960s, Choi has made around 250 guqin. Now aged 90, he spends most of his time overseeing his apprentices as they make instruments of their own, and, within the confines of his modest workshop, this old art form continues to enjoy new life.