Happy hermits

Sometimes, users praise his cooking. Other times, they chat with him about recent happenings. And many times, there's no response at all.

But no matter what, the group offers him some kind of satisfaction.

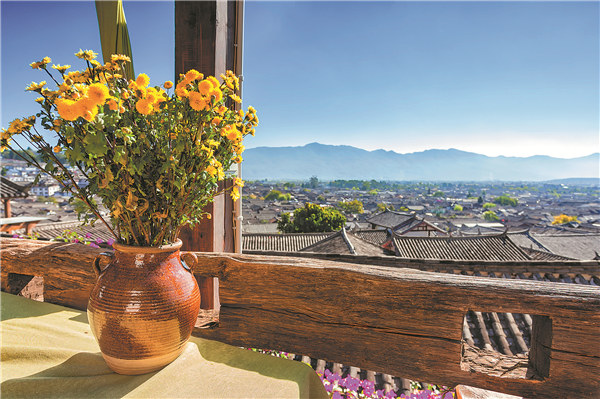

Zou's favorite in-person social activity is watching the local torch festival. The flames carried by crowds light up the land like stars and illuminate the night sky. Two-story-high torches stand on the street corners. And young people sing and dance around bonfires while smearing one another's faces with ashes to convey blessings.

As the number of "hermits" in "Yinju Ba" grows and many of them are young like Zhang and Zou. Their typical motivations are also changing with the times.

The earlier practitioners were more like homesteaders, who left cities to work from sunrise to sunset to build houses and farms in remote areas — a lifestyle that's not only old but ancient, as recorded by Eastern Jin Dynasty (317-420) poet Tao Yuanming (365-427). And this way of life is certainly busy, although self-reliant, rather than hectic and highly interdependent like people in cities.

Compared with the escapism of fleeing the pressures of urban life that largely defined the trend a decade ago, today, more young people are "lying flat" in small settlements as acts of spiritual rebellion, to find peace outside of society's confines.

Zhang doesn't know how long his seclusion will — or, ultimately, can — last. But a decade into the experience, he's not worried about this aspect of his future.

He recalls the words "Yinju Ba" users offered him a decade ago that changed his life in ways that have lasted until today: "Seclusion is a process of inner cultivation — not of escape."

Yan Bingjie contributed to this story.