On China, Washington 'can't have it both ways'

For a period of time, Washington has been sending mixed messages to China: seeking cooperation and communication while containing China in the name of "competition."

Those paradoxical statements and actions reflect an increasingly clear tendency in Washington's China policy: to compartmentalize its relationship with Beijing into different categories, where it can apply an approach of containment, competition or cooperation according to America's needs.

Decision-makers in Washington could be thinking that each of these different tracks can work perfectly well without rocking each other, and that China should just accept the arrangement as a matter of course. Seriously, this is purely deceitful thinking. It is like stretching out one hand for a handshake and saying "let's work together," and then slapping the person in the face with the other and expecting the slapped to just smile.

The United States was once treated in a similar manner during the Cold War. Back in the 1970s, its European allies wanted US assurances on security but were "less cooperative" with Washington on the economic and diplomatic fronts. Frustrated, then-US President Richard Nixon said that "they can't have it both ways -- they can't keep our forces up and confront us everywhere else."

Therefore, when demanding communication and cooperation from China and almost simultaneously interfering in China's internal affairs and hurting China's interests, Washington should have little difficulty in understanding why China categorically says: "You can't have it both ways."

Such a patchwork of containment and engagement in America's China strategy is not new. Almost every US administration since Bill Clinton adopted such a two-pronged China strategy until recent years when the argument of "the failure of engagement" seems to have gained an upper hand.

In its design, the United States wants in the post-Cold War era to manage China's development, and turn the country into its junior partner -- a huge market for US products, services and capital, a source of affordable resources for US industries, and most importantly, a minion who could deliver on America's priorities. China can grow but must grow on the track set by the United States, and certainly not to the extent that the US supremacy might be challenged. To put it simply, the Chinese should just keep their feet on the ground and manufacture T-shirts and socks for American consumers, instead of trying to move up the "smile curve."

This is in no way an equal relationship, which is reminiscent of Washington's overbearingness in international relations. In its eyes, China's rapid rise was made possible by America, and Beijing should be grateful.

This murky motive explains why Washington has always talked about "approaching China from a position of strength," and why some US politicians have voiced their frustration or even anger when they see a prosperous and ever-developing China still firmly striding on its own path without being transformed according to Washington's design.

However, in a highly integrated world, a complete US decoupling from China is as impossible as it is disastrous. Washington knows that quite well. That explains why US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and US Trade Representative Katherine Tai recently denied that their country was seeking to decouple the US economy from that of China.

Moreover, global challenges like climate change need global solutions. But as Washington insists on hammering China in areas like high tech under the guise of "national security" and making provocations on China's red line, it is ruining the conditions for both sides to work on some of those urgent planetary crises.

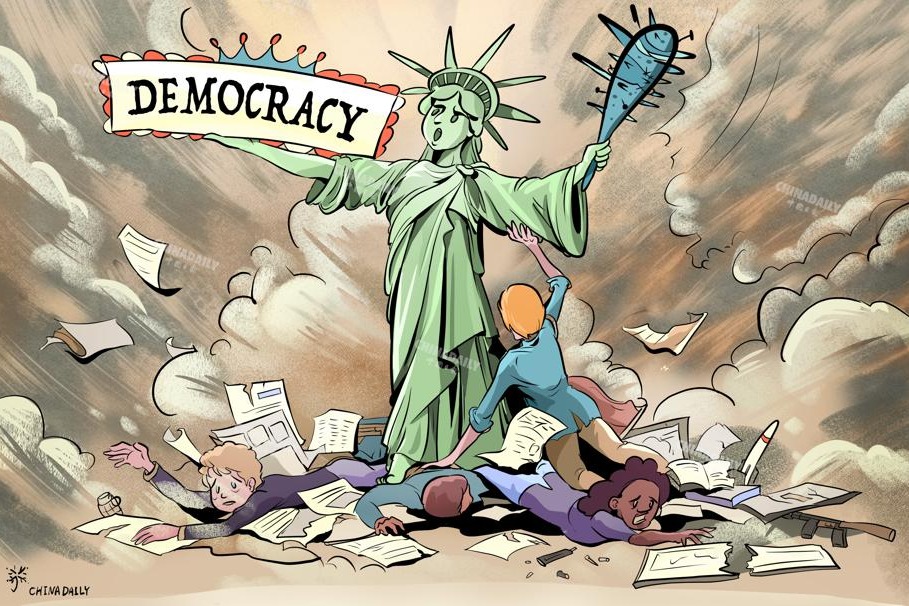

Still, to confuse the world's public opinion, Washington is peddling the so-called "democracy vs autocracy" narrative, and portraying China as a "revisionist power," while claiming that it is safeguarding a "rules-based world order" and protecting "human rights." Such a sanctimonious approach to handling the relationship between the world's top two economies is highly irresponsible and reckless.

In the immediate days following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia and the United States enjoyed a honeymoon period. The Charter for American-Russian Partnership and Friendship signed by the two sides in 1992 said "the well-being, prosperity, and security of a democratic Russian Federation and the United States of America are vitally interrelated." However, things changed when Washington failed to provide Kremlin with the promised economic aid and NATO expanded despite Washington's promise that the bloc would move "not one inch eastward." This was unacceptable to Russia, and the ensuing deterioration of Moscow-Washington ties was only natural.

Deep down, America had never intended to treat Russia with respect even though Western-style democratic elections took place in the country. Ideology is just an instrument to intervene.

For Beijing, Washington's condescending diplomacy is unacceptable. If Washington truly wants a workable relationship with China, it should treat China as an equal partner and show due respect.