Reforming cultural exchanges to help build stronger trust

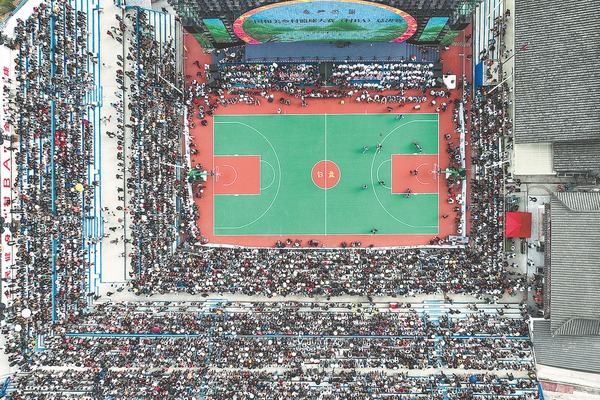

The term "cultural diplomacy" is no neologism. Indeed, cultural diplomacy has long served as a core pillar of "track-II diplomacy," for example, engagement and exchange efforts between private citizens and individual actors. Ping Pong diplomacy qua sports/cultural diplomacy, too, played a pivotal role in reopening dialogue between China and the United States in the early 1970s.

For all the talk of "people-to-people exchanges" as per the China-proposed Belt and Road Initiative, and the US' emphasis upon "cultural and educational visits and tours" to China — one could be forgiven for thinking that the state of apolitical, nonpartisan cultural ties straddling the two sides of the Pacific would be relatively robust.

Yet despite the historical depth and genuine goodwill that was built up over the past decades, through the efforts of individuals seeking to foster better understanding and interlocution between Chinese and US citizens, the past few years have seen a precipitous decline in exchanges of this nature. Routine, innocuous performances of certain plays, set pieces, or music with certain political connotations that may not conform to orthodoxy, have become invidious ticking time bombs for both performers and audiences alike.

Similarly, previously active people-to-people channels and discussions on culture, as well as artist-in-residence exchange programs, have slowed down considerably under suspicions of alleged espionage or infiltration.

Let's face it. As things stand, cultural exchanges between the US and China are facing some rather treacherous and pronounced headwinds, and solving the problem is a prerequisite to restoring some semblance of normalcy in bilateral cultural ties.

Concerns about perceived political and national security risks are surrounding cultural exchanges and related institutions. That Confucius Institutes-broadly innocuous language-teaching institutions that nevertheless do adhere to certain stipulated boundaries and regulations concerning their contents and approaches to teaching — are now painted as vehicles for intelligence gathering is indicative of two fundamental facts. One, that there exists a significant volume of mistrust and uneasiness toward the presence of Chinese organizations or institutions, so long as they could be viewed as remotely affiliated with the state (even though such ties may not, as it turns out, necessarily hold). And two, that the Chinese government must take seriously the root causes for the extremely mixed and at times hostile reception toward its international cultural presence.

The dangers of over-securitization also apply to the way Chinese authorities engage with "Western" non-government organizations dubbed to be promoting cultural values and norms that are antithetical to the dominant zeitgeist or mainstream thought in China. It is necessary to recognize that the basis for cultural exchange is frank, open conversation and debate, and such conversations and debates cannot occur unless the state — especially one with incredibly potent apparatus — creates breathing space for such candid talk.

The deterioration in Sino-US relations over the past few years has rendered many in the field of arts and culture who straddled "both sides" feeling deeply perturbed. The hope is that with the meeting between President Xi Jinping and US President Joe Biden on the sidelines of the G20 Summit in Bali, Indonesia, on Nov 14, a degree of normalcy and trust could be revived in the relationship.

Both China and the US appear to be savvy enough to navigate both sides. On the Chinese side, there is a growing tendency to view cultural exchanges as opportunities to advance "correct values".

The best means for China to tell a "good story" about itself is through empowering and embracing the cultural grassroots and "fringes".

The same, of course, could be said of the pressures applied on cultural exchanges on the US side, where cultural, academic and art-based exchanges with China have either dwindled in numbers and intensity, or have been disproportionately criticized by politicians who endeavor to besmirch such exchanges as efforts to co-opt and destabilize. Such McCarthyist rhetoric would only drive away the many artistic and cultural talents born in China.

So what gives? Two preliminary thoughts and suggestions. The first is that cultural diplomacy should be championed and driven by cities, as opposed to countries. National governments tend to be bogged down by political considerations, and constrained in the range of options they can concurrently pursue. Cities, on the other hand, are far more flexible.

The second, is to devolve the leadership and spearheading of cultural exchange policies to private citizens and individual artistic-cultural groups. Track-II diplomacy is best left to the second track — the societies and performers acting according to their own volition, as opposed to particular state mandates or recommendations.

The author is Rhodes scholar at Balliol College, Oxford.

Source: Chinausfocus.com

The views don't necessarily reflect those of China Daily.