Uncertain and afraid? I was too, but with hurt also comes healing

To say 2020 has already been an eventful year would be an understatement, and my journalistic instincts tell me that more decade-defining events might be around the corner. Haunted by this idea in recent weeks, my thoughts kept returning to a poem written by W.H. Auden as World War II began in Europe, called September 1,1939: "I sit in one of the dives. On Fifty-second Street. Uncertain and afraid. As the clever hopes expire. Of a low dishonest decade."

In the almost three decades I have been on this planet, I have never experienced until now how precarious life can seem. Perhaps it has something to do with me becoming a father in late March as the world spiraled into one of the worst pandemics in modern times.

Many experts I interviewed during the two sessions told me that the world may never be the same after COVID-19, not just in terms of geopolitics, but also in the way we live our lives and navigate complex and often contradictory needs and emotions.

One example is how we relate to others. Social distancing has brought families physically closer, but domestic violence and divorce are also on the rise as an unfortunate consequence.

Science and technology have made life under quarantine easier through digitized services. But I can't shake the feeling that humanity has never been further apart, like everyone is living on their own private island and interacting via cold binary code, rather than making real connections with people.

To tell the truth, I was a bit nervous when I first discussed these human conditions with members of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference National Committee, thinking that they might be too busy for these possibly pretentious and certainly sentimental observations.

To my great surprise, many members, from artists to scientists, told me that they had been pondering the same questions. Many have even dedicated their proposals this year to overcoming these issues and want to preserve the legacy and knowledge of the COVID-19 pandemic to help in similar outbreaks in the future.

Wu Hongliang, president of the Beijing Fine Art Academy, said the COVID-19 pandemic can not only undermine people's physical health, but also their mental wellbeing. As the epidemic fades in China, Wu hopes the mental health of members of the general public gets the attention it rightfully deserves.

"We need to find ways to tap into the healing potential of artistic expression and use it to mend the mental scars left by the pandemic," he said.

As a result, Wu proposed to the annual meeting more painting courses for elementary and middle schoolers, as well as commissioning public art pieces to preserve the memory, struggle and triumph of the people against the disease.

Tong Guohua, the board chairman of the China Information and Communication Technologies Group Corp, said the issue he is losing sleep over is how to protect the enormous amount of personal data collected throughout the epidemic.

"We have collected many types of data including addresses, contact information, ID numbers, family members' information, medical histories and others," he said. "This data is being stored across different layers of society from booklets in local community offices to databanks of government agencies," he said.

"What do we do with this data once the epidemic is over? How do we protect it from hackers or illegal use? These are the questions scientists and engineers must solve soon," he said.

Huo Yong, a noted cardiologist at Peking University First Hospital, said some social mechanisms established during China's fight against COVID-19 should be continued and optimized to cover chronic illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, cancer and diabetes.

These mechanisms include better prevention and early detection measures, massive scientific outreach and public education campaigns, and close monitoring of patients.

"The COVID-19 epidemic has killed over 4,000 people in China. Cardiovascular disease kills more than 4 million people in China every year, yet many people do not take it as seriously because it is a chronic disease that kills over time," he said.

Over 60 percent of patients who died from cardiovascular disease died outside of hospital care, he added. "If we can have more people who can spot troubling symptoms, or know how to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation, we can save a lot of lives," Huo said.

- New rare crab on the tongues of gourmet chefs

- International students envoys of Chinese culture

- CGTN documentary on fighting terrorism: Darkness over Urumqi

- Giant panda pair gifted to Hong Kong come out of quarantine

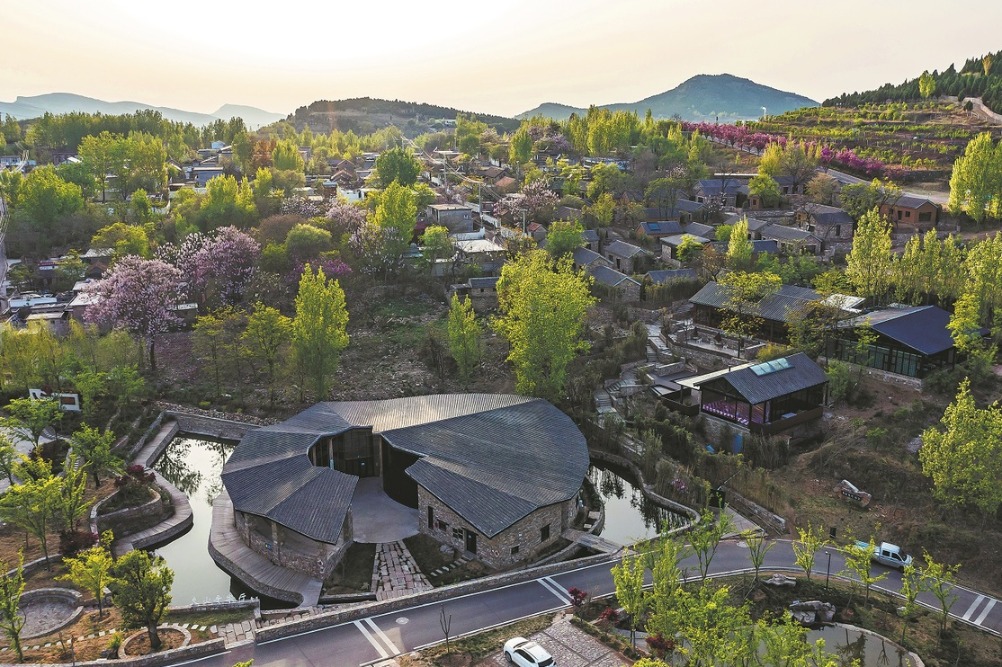

- Rural China becomes a hotspot for young people

- Global smart grid offers solutions to climate change, biodiversity loss