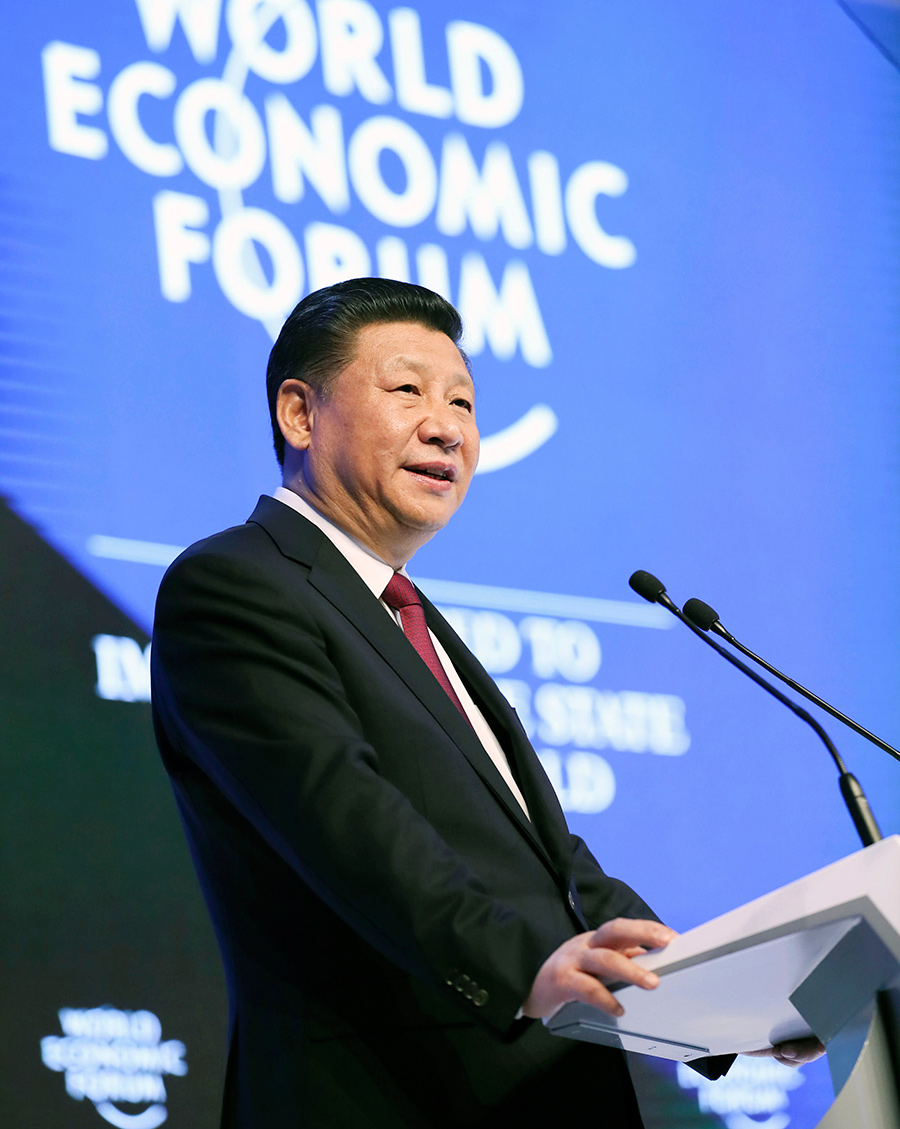

One year on, impact of Xi's agenda-setting Davos speech still felt

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s speech to the Davos World Economic Forum one year ago, on January 17, 2017, decisively shaped international discussion - the US magazine Newsweek summarized its impact as being that China was now seen as: “the linchpin of global economic stability.” Ian Bremmer, head of the Eurasia Group, the most influential Western “risk analysis” company, noted: “Davos reaction to Xi speech: Success on all counts.”

This impact has increased. Analyzing the 19th CPC Congress the Financial Times summarized: “Mr Xi has clearly had a very good year, beginning with his January address to the World Economic Forum in Davos.” The announcement President Trump will speak at Davos this year in large part reflects the impact of President Xi’s speech last year.

Given this speech’s great influence in shaping international discussion it is important to understand why it made such a deep international impact.

The first, most important, reason was naturally its content – an unequivocal explanation of the fundamental concept of China’s policy of a “shared future for humanity” and its conclusion that China’s foreign policy seeks “win-win” solutions between countries and rejects international relations as a “zero sum game”.

The speech noted how this flows directly from globalization’s nature: “Economic globalization is a result of growing social productivity, and a natural outcome of scientific and technological progress.”

The Chinese dictum “seek truth from facts” confirms this. Numerous factual studies demonstrate the positive correlation of an economy's international openness and its development speed. Growing globalization was decisive during the global international economic stability and growth after World War II – in contrast 1929-39’s global economic fragmentation created the greatest crisis in modern history.

Given economic progress’s dependence on globalization, maintaining an internationally open economy is therefore vital not only for governments but for the world's people. Globalization has brought immense benefits to the majority of the world's people, strongly confirming economic theory. Certainly, China decisively took advantage of globalization's benefits – achieving since 1978 the world's most rapid rise in living standards, while 75 percent of those in the world lifted out of poverty were in China.

But other countries also strongly benefitted. India has now consciously learnt from China's economic model of opening up and African countries basing themselves on globalization have achieved growth rates of 6-9 percent a year.

President Xi’s Davos speech therefore clearly articulated how globalization simultaneously corresponded to China's national self-interest but also to the national self-interest of other countries. That mutual self-interest is the firmest of foundations for cooperation is why the speech was widely characterized as embodying “global stability”.

The second reason for the speech’s great international impact was timing. For most of the post-World War II period the US supported globalization – playing a key role in agreements culminating in the creation of the World Trade Organization. But, regrettably, recently protectionist voices have become more vocal in the US. It is to be hoped protectionist words are not turned into actions but many countries believe there cannot be 100 percent certainty that the US retains a commitment to globalization.

Because Xi’s Davos speech made clear China remains unequivocally committed to an open international economy, China emerged as the largest economy committed to globalization and “win-win” development. The great majority of other countries understood the importance of globalization for themselves and therefore agreed strongly with Xi's statements.

Finally, the speech was extremely skillfully presented. Naturally, as China’s president, Xi Jinping made extensive reference to classical Chinese authors such as the Book of Rites. But the speech was equally understandable in a Western idiom, quoting Dickens and strikingly explaining the theoretical underpinnings of economic openness's advantages.

The first sentence of the founding work of modern Western economics, Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations, is, "The greatest improvement in the productive powers of labor … have been the effect of the division of labor." But division of labor in a modern economy has reached a point where it is necessarily international – attempts to create self-contained economies therefore necessarily fail.

Given how fundamental the issues Xi Jinping’s Davos speech dealt with are to the present world its already great impact will continue to increase.

John Ross is a senior fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. He is also the former director of Economic and Business Policy for the Mayor of London.