hotrecommend

New lease on life

By Guo Shuhan (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-05-19 11:22

|

Large Medium Small |

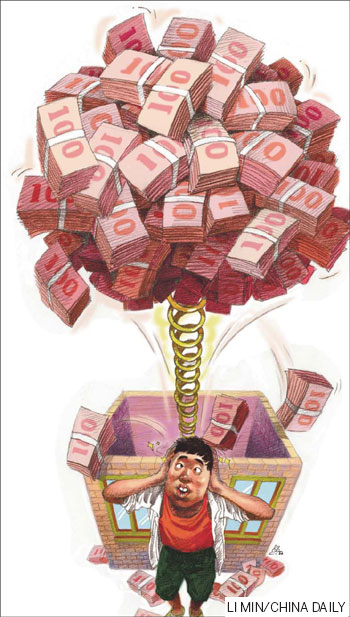

Relocation compensation is the key to a new life for many, but not all recipients find it easy to adapt to an affluent lifestyle. Guo Shuhan reports

| ||||

Every evening, Zhang is back in his expensive clothes, dining out with his bank-clerk girlfriend - who hides his occupation from her friends - then it is off to the pubs and coffee bars till late into the night.

The son of an ordinary farmer, living on the edge of Zhengzhou, Henan province, Zhang now works for the bus station, making 1,100 ($161) per month, an amount barely enough to pay for the petrol of his luxury car.

But while Zhang's income may not amount to much, he is one of the growing ranks of China's newly affluent who have benefited from the nation's rapid urban expansion.

Since the late 1990s, villagers living in prime locations have been receiving compensation for relocation. This is often in cash or kind, sometimes both. When the compensation is a flat - or several of them, as in Zhang's case - the beneficiaries frequently lease or sell them, making considerable money in the red-hot property markets of the big cities.

Zhang's family used to live in Zhengzhou's Xiguanhutun village, until 2007 when their house was demolished to make way for the International Trade Center.

According to figures from Zhengzhou statistics bureau, the annual per capita disposable income for urban and township residents was 17,117 yuan in 2009.

In contrast, Zhang's family makes around 240,000 yuan ($35,160) a year from the rental on six of the flats they received as compensation. Were they to lease the flats for commercial purposes, the income would be even higher.

Cao Tian, general manager of the Zhengzhou Fengyasong Real Estate Company and developer of one of Zhengzhou's new neighborhoods, Liulin, estimates that around 40,000 of the 100,000 residents in 15 Zhengzhou redevelopment projects are in the same position as Zhang.

Zhang Yi, a researcher with the Institute of Population and Labor Economics affiliated to the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, says while there are no specific nationwide figures for the number of farmers who have benefited from redevelopment compensation, the phenomenon is more likely to be seen in two kinds of cities.

The first is cities where the government offers high compensation. For example, in Shanghai, in Luwan district in the city center, compensation for 1 sq m can be 30,000 yuan.

The second are cities lacking strict building height restrictions such as Shenzhen and Guangzhou. Here, residents develop their houses, so that in the event of redevelopment they can get a higher compensation, which is usually determined by calculating the floor space.

In Zhengzhou, Zhang's family added another six floors to their 2-floor terrace, for a floor space of more than 1,000 sq m.

But as Zhang has discovered, such new-found wealth can be a mixed blessing. For years, the junior high school dropout worked as secondhand house agent, for a monthly salary of a mere 2,000 yuan, until he decided it was too much work and quit.

After receiving the compensation, he stayed at home for a year, but tiring of such a dull life, he attended a training course to qualify for his current job. "At least I have something to do. And I just need to work half the day," he says.

Zhang is not the only one with a newly acquired affluent lifestyle who is struggling to come to terms with it. Lacking much education or even specific skills, most turn to business, says Li Ling, a journalist with Oriental Today who has visited more than 20 demolished villages in Zhengzhou. Some end up throwing away their money on drugs, gambling or get involved in dodgy pyramid-selling schemes, Li says.

"They have no idea where to start," says real estate developer Cao Tian, who is also a member of Henan Writers Association.

Some, influenced by their elders, are too conservative to think of change and continue with their old lifestyles despite having more money.

"We continue to see ourselves as workers," says Li Yongchun, a second-generation farmer from Guangzhou, Guangdong province, and one-time resident of Liede village of the new urban region of Zhujiang.

Besides financial planning, researcher Zhang Yi says those in receipt of compensation also need help with managing their riches and integrating into urban life. "Otherwise, they may not adapt well into a new environment and will be isolated," he says.